Have you felt at peace?

What a standardised question reveals about how we engage with life and death

A few years ago I had the privilege of sitting with a dying woman as she was being cared by a nurse in a London hospice. She was in her mid-50s, living alone in a rented room with terminal cancer. I couldn’t really tell she was coming to the end of her life, until she described how she felt.

She was asked about various things about her physical symptoms (her pain, her bowel movements), but then she was asked whether she felt at peace.

Much to my surprise, she was. Despite her pain, despite her lonely situation, despite everything that might indicate otherwise, she was at peace.

How she came to be at peace, has remained with me since, and helped me want to understand how we come to find acceptance and peace in our lives.

The thing is, for all its grandeur, the question “have you felt at peace?” is a standard one from a clinical measurement tool called an Integrated Palliative Outcome Scale or IPOS.

IPOS contains items considered most important to patients and families (such as pain, breathlessness, anxiety, and information needs), but also in relation to their healthcare provision (for instance, breathlessness is one of the commonest reasons for emergency admission). It also includes the 'at peace' question as this globally reflects psychological and existential domains across diverse backgrounds, cultures and beliefs.

Asking these questions are important because palliative care professionals want to understand a person’s holistic needs - their physical, social, psychological and spiritual needs. They want to ask people how they feel - in all the various ways they feel about things - so they can help them.

These conversations at the end of life are important, and palliative care professionals are the best at it. They can navigate the ambiguity, the uncertainty, the emotions like masters.

However for the rest of us, asking these kinds of questions that important when living with a terminal illness or being near death - in the way that normal people would ask them - can be really difficult.

Age UK, the leading charity for older people, did some research on it and found that:

Over a third (36%) of people aren’t comfortable bringing the subject up with a relative or close friend and 40% don’t know their loved ones wishes around dying (such as what their preferred type of burial might be).

It seems that for us amateurs, we just find it hard to talk about death.

Like a cold water wave across the bow

In the death-and-dying world (as I call the palliative/end of life/hospice/death care space) the mantra for the last few years has been: we need to talk about death. It’s been pretty singular in that respect.

It’s why Death Cafe’s exist. There are many projects dedicated to it. It’s something I’ve done a lot of my own work around. Hell, there are even card decks designed to help us to talk about it.

But I think there’s a problem with all of this.

However it’s not about what decisions are made, as a result of talking, and are often ignored. It’s about the fact that just talking about it, doesn’t help us with the deeper problem: that when we talk about death, it awakens a deep anxiety in all of us. A death anxiety.

As you might imagine, this is no ordinary anxiety. And as someone who lives with the various forms and guises of anxiety, I feel I can talk about the difference. This type of anxiety runs cold and deep. It’s primal. And it packs a wallop.

In fact, for someone living with a terminal illness, or confronted with a final prognosis, the realisation and feeling of their morality can cause an existential slap:

[It’s] the moment when a dying person first comprehends, on a gut level, that death is close.

It is a critical moment in your life when you recognise, in a deep felt sense, that your time is limited, that your body has a physical end point, and there will be a time when you will be no more.

Knowing that death is close, is a moment that will happen to all us (bearing unexpected accident or tragic injustice). But what it does to us varies across our cultural, religious or intellectual backgrounds.

For the woman I was with in that London hospice, she had felt it, she was slapped by it. But in her case, she used quantum physics to grab and wrestle with it.

When we had a moment, and while the nurse was out the room to confirm another appointment, I asked her what had helped her feel at peace. She took a book out of her bag: Carlo Rovelli’s 7 Short Lessons on Quantum Physics. She told me:

I needed to find out how things worked! My intuition guided me to these books. I have no fear. When you know how things work, you’re not afraid.

As a self-professed atheist I was impressed. She was previously religious, but now took meaning from cutting-edge science to understand what was going to happen to her once she died: her matter would transform into something else. Broken down to components, scattered and re-used forever. That’s one way of thinking about ‘life after death’.

At the time I thought turning away from religion would make the experience harder for her. Don’t religious people tend to be at peace at the end of their life? Apparently not.

Being religious is not a good guard against death anxiety: studies show that ‘if the fear of death motivates religiosity, it does so subtly, weakly, and sporadically.’ It does not provide a straightforward antidote to the fear of death.

She was making sense of her own death, in her own way, without religion.

But for me, in the moments after, when the nurse came back in the room, I felt it. A big, cold wave across the bow. It is not a pleasant experience. Whoa, this really will be me one day. I have to die at some point.

Making meaning out of fear

Because the thing is, death anxiety is not limited to dying people. It’s not just about the feelings that come up while living with a terminal illness. It’s bigger than that. The prospect of death is terrifying regardless of how close we are to it.

It can sour the brain and deeply affect our mental health. So much so death anxiety can express itself across multiple mental health disorders. It is, in the lingo, a transdiagnostic construct.

Death anxiety is considered to be a basic fear underlying the development, maintenance and course of numerous psychological conditions, and it is not uncommon for psychologists and therapists to encounter individuals who struggle with the concept of death.

I don’t think it’s too dramatic to say we are constantly facing the prospect of our death. It’s just done in a very subtle way.

I mean, have you read the news at any point, in say, the last year? It can feel pretty grim, pretty easily. There’s a lot to feel existentially afraid of at the moment, with good reason.

On top of that, we’ve gone through a pandemic. A pandemic whose daily machinations was played out with a persistent tracker of daily deaths. What was previously hidden was now playing out in real time. People are dying, you’d see over your breakfast coffee, every day!

And this knowledge - this exposure to the reminder that we are mortal and will die - it pains us.

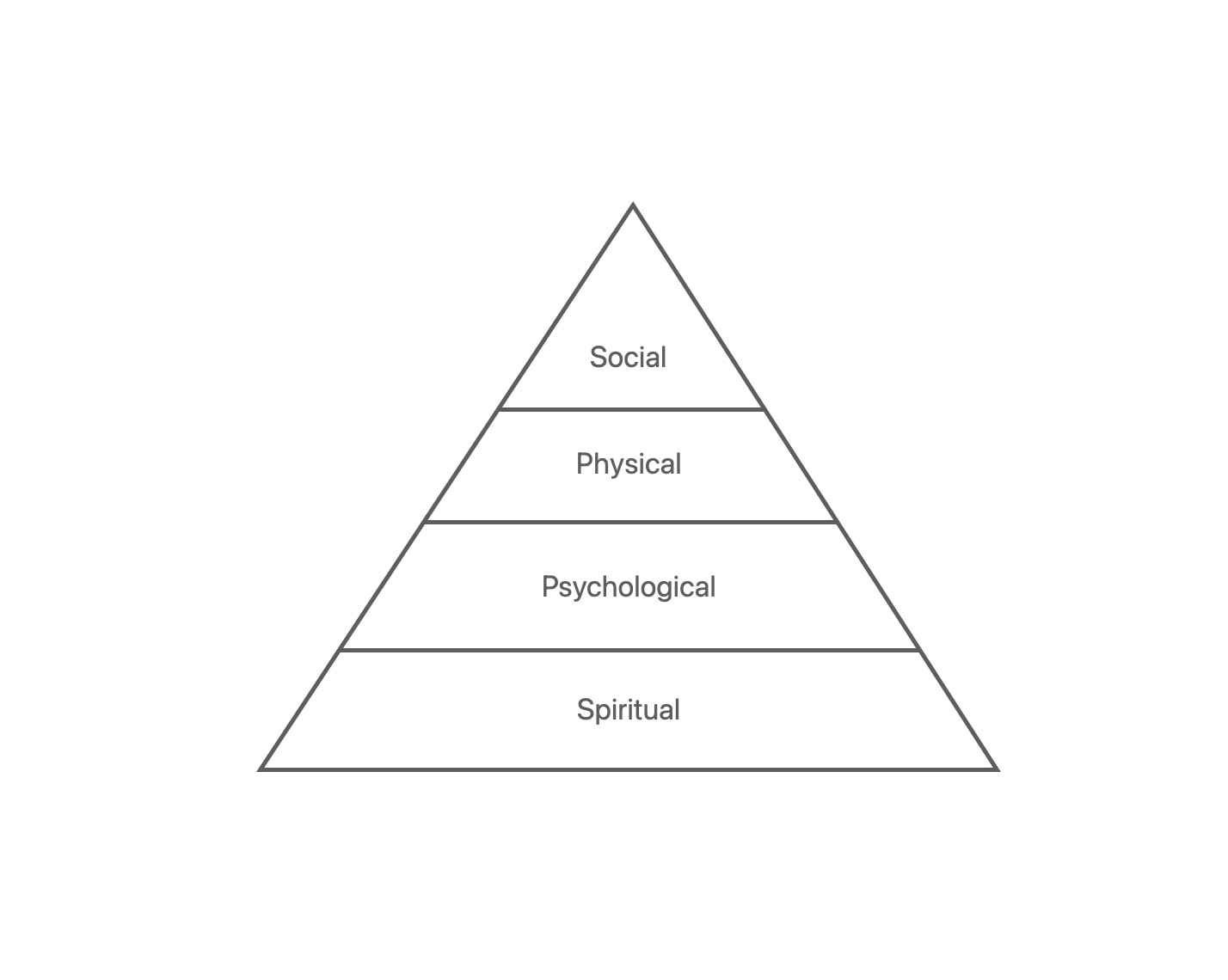

Cicely Saunders - the pioneering hospice nurse who founded the modern hospice movement - created a framework to understand how someone experiences ‘total pain’. That is, how they feel and suffer in a variety of ways, from their physical symptoms to their social problems. How they suffer spiritually, was deemed to be as important as their physical pain from their cancer tumour, or loss of family connection. Importantly, it was ordered as a whole divided in four, all equal.

However, I don’t think they are equal.

Knowing we will die is a pain that operates at a deep, existential, spiritual level. If death anxiety is the cold wave across the bow, then spiritual pain is the quiet, dark oceanic current beneath the waves. I think it sets the foundation for everything else. It’s the thing that keeps us up at night thinking: Why am I here? Is this it? What will happen next?

But if – faced with our death in a small or big way – we can somehow confront how our mortality pains us at an existential level, then we are open and ready to confront all other aspects in a more whole way. If religion doesn’t really give us much defence, maybe it’s something else. Because I think that if we can relieve any spiritual, existential pain, then we can deal with everything else.

So instead of all parts made equal, what would change if we placed spiritual pain at the bottom of the pile?

I think it would change how we engage with our mortality. It would re-frame the conversations to ask the deepest questions first: Have you felt at peace?

Because otherwise, how can we talk about what we want in life, if we can’t make deep sense of it first and talk about what it means?

You can’t be expected to talk about the kinds of decisions that you face as a dying person (what kind of treatments you want, what your preference for treatment if this or that horrible thing happens to you, or that unfortunate complication makes death more likely) without first tackling how facing our mortality makes us feel, and how we make sense of it.

Talking about death through the lens of what literally happens to you, is the same as talking about the fact the world is on track to warm beyond the critical 1.5º. It doesn’t actually mean that much in and of itself. It’s just some functional information.

But engaging with what it means to face mortality and to confront those feelings, is the same as engaging with the fact that rising ocean levels will not just displace you and your family, but that your dear ancestors will also wash away with the tide.

It goes deeper, and asks a more important question about what it is to be human, to be part of something bigger than yourself, to engage with what we consider immortality or immutability.

Let’s start talking about the deep, spiritual stuff, and everything else will fall into place. Who knows, maybe it will - like many people say - give us a zest for life that cannot be provided any other way.